test

Grown Up from the Earth:

A Conversation with Martyn Cross

Martyn Cross is a British artist, known for his paintings that explore the Medieval and the modern in equal measure. Through worn-down, weathered canvases depicting expansive landscapes, nature spirits, or mysterious creatures, he combines a contemporary, sometimes cartoonish sensibility with a suggestion of ancient meaning.

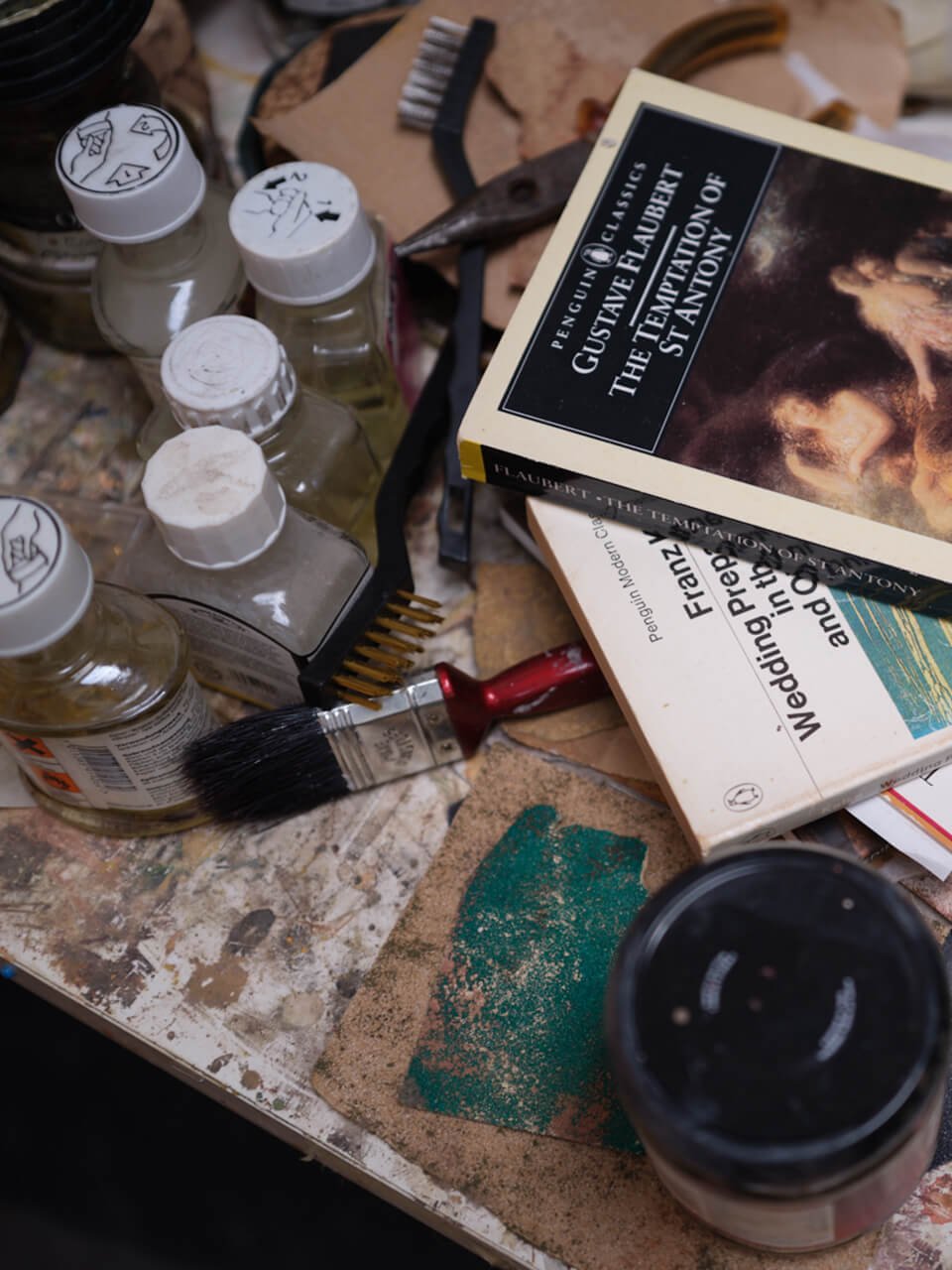

We recently caught up with Martyn to chat about texture and subject matter, as well as how Flaubert and childhood doodles find their way into his work.

I’ve read that fiction tends to be a big influence when starting a new painting. Could you explain what it is about certain passages of writing that get the ball rolling for you?

With fiction you become immersed in something, and it’s very much about your own imagination, and there will be certain fiction that will take you somewhere else entirely, to a different plane, almost. I read a lot, but it’s probably only one in every twenty books that might have that little nugget that’s just like, ‘Yes, that’s something.’ And I might not use it for a long time. It’s just there, bubbling. And it might be in a year’s time where I suddenly access that thing.

I’ve read that fiction tends to be a big influence when starting a new painting. Could you explain what it is about certain passages of writing that get the ball rolling for you?

With fiction you become immersed in something, and it’s very much about your own imagination, and there will be certain fiction that will take you somewhere else entirely, to a different plane, almost. I read a lot, but it’s probably only one in every twenty books that might have that little nugget that’s just like, ‘Yes, that’s something.’ And I might not use it for a long time. It’s just there, bubbling. And it might be in a year’s time where I suddenly access that thing.

A lot of your work deals with the natural world. Do you find yourself inspired by your immediate surroundings? Where are you, by the way?

I’m in Bristol, in the city centre, practically. So, it’s interesting you say that. I know my work features a lot of horizons and nature, but it’s probably not inspired by what’s immediately around me. But whenever I leave the city, I will always seek the sea, horizons, that expansive experience when you’re out in the wild. That’s something that will stay with me, and I can draw upon it for making paintings.

And talking about the paintings themselves, could you tell me a bit about the texture of the work, because they all look incredibly worn down and weathered.

Yeah. I have a physical relationship with the work, and so that physicality, from the prepping of the canvases, through to holding the canvases when they are small works, you’re having a relationship with them. And there’ll also be the flip side to that where I will be aggressive with them sometimes: I will be rubbing them down with rags and I will be kicking them about the studio in some shape or form, having a kind of full-on workout with them, and I feel that’s incredibly important for those works to absorb that. I like scuff them up a bit, and to give them some kind of life. I don’t really like slick paintings, I quite like stuff that’s a bit ramshackle, that may look like it’s been found somewhere, rather than it being produced. To look like it’s grown up from the earth, or been found in a corner in an alleyway or something [laughs]. And quite why that is I don’t even know [laughs], but that’s just my preference, I suppose.

I’ve seen your work described as melancholy a few times, which I think is certainly true in some places, but I find a lot it to be very inviting, and maybe even slightly mischievous or humorous at times. Is that a conscious thing, or something that just comes out in the work?

I think it does just come out, in a way, although I don’t like it when art or painting becomes too serious. I try and steer away from taking myself too seriously. Ultimately, I want the paintings to be accessible, and I don’t want to just be catering towards an art audience, I want to be talking to a lot of different people. I think, if you’re too serious about what you’re doing, it just makes the work really leaden, and I want my work to have all those elements that you’ve just described. I want it to be stupid, I want it to be dumb, I want it to be about experiences that we have that can be incredibly sad or depressive, but there’s always gonna be something kind of light in there as well.

I’m inspired by a lot of artists who have used cartoon imagery, so someone like Philip Guston immediately springs to mind, or maybe Brian Calvin is another one, Jean Dubuffet. I really like that loose, cartoony quality, and it’s something that I’ve accessed more recently. I encountered some old exercise books – I was one of those boys who used to draw all over my exercise books [laughs] – and it was a bit of a lightbulb moment. I was suddenly like, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s what I used to do, and I really enjoyed that.’ There was a freedom, because as a child you can just doodle away, whereas when you’re older and you’re needing to get paid to make artwork, you don’t necessarily have that looseness with what you make. But when I had this lightbulb moment, it suddenly opened up a whole different way of working for me, I became a lot looser, and I started having more fun. Prior to that I was getting a little bit tight with what I was doing, it was becoming quite prescriptive. So that style shift has been really important to what I’m doing right now.

Finally, how does your studio space shape or influence the work?

I changed studios a couple of years ago now. I was working in quite a dark, dingy space before, and the studio I’m in now is very light and bright, and I definitely felt a shift when I moved from one space to another. Things started changing in terms of how my work was being seen by other people, and I was getting a lot more feedback, I was speaking to a lot more people, and I felt there was a lift in colour, in the paint I was using. I don’t think I necessarily thought that changing studios would do that, I never really considered how much a space can influence what you’re doing. I had a residency recently and I found it really difficult to start making work in that space, because it was a new space to me, and it was completely different to my usual setup.

The actual studio practice itself is really important. When I go into the studio, I might not make work for hours, I can just be sitting there, looking at what I’ve been making, and communicating with those paintings in some way. You’re processing in your head what’s happening, and then you might go and pick up some paper and start doodling, and those doodles then go on to make a painting. But it's important to have everything accessible around you. Even working towards a show, I don’t change my space much, and my space gets quite messy. Then when you have a show and you clear out a lot of artwork, I’ll clear up the space so it’s brand spanking new, almost. And then you’re kind of starting again. But I really love a messy studio. I think it’s important to be within your mess and just to let things grow up from that, quite organically [laughs].

Martyn Cross lives and works in Bristol. He has displayed his paintings in solo exhibitions in the UK and US, and has upcoming shows at Hales Gallery in London, and Marianne Boesky Gallery in New York. Shop new season arrivals